#jagged little pill era

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#bc I can#and bc I love him#taylor hawkins#my gifs#jagged little pill era#alanis days#alanis morissette

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

the day i find a cheap tuck everlasting cd is the day it's all over for you bitches 😎

#tuck everlasting#im in my cd era#bought like 8 second-hand cds for like a buck a peice today#they had alanis morissette jagged little pill in the clearance section for a buck and i was pissed

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hottest Drummer Tournament Round 1

Animal

Band(s): Dr. Teeth & The Electric Mayhem

Albums/EPs as drummer:

You Are The Sunshine Of My Life (Jack White and The Electric Mayhem) The Electric Mayhem (Dr. Teeth & The Electric Mayhem)

A Christmas Together (John Denver and The Muppets)

Taylor Hawkins

Band(s): Foo Fighters // Taylor Hawkins and the Coattail Riders // Nighttime Boogie Association // NHC // The Birds of Satan // Dee Gees

Albums/EPs as drummer:

There is Nothing Left to Lose (Foo Fighters) One By One (Foo Fighters) In Your Honor (Foo Fighters) Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace (Foo Fighters) Five Songs and a Cover (Foo Fighters) - drums on all tracks but 5 Wasting Light (Foo Fighters) Saint Cecilia (Foo Fighters)

Taylor Hawkins & The Coattail Risers (Taylor Hawkins & The Coattail Riders) Red Light Fever (Taylor Hawkins & The Coattail Riders) Get the Money (Taylor Hawkins & The Coattail Riders)

The Birds of Satan (The Birds of Satan)

Intakes & Outtakes (NHC)

Taylor Hawkins (solo) Kota (solo)

Jagged Little Pill, Live (Alanis Morissette) Good Apollo, I'm Burning Star IV, Volume Two: No World for Tomorrow (Coheed and Cambria)

Propaganda:

drummed on tour for alanis morissette jagged little pill era

#Animal muppet#Taylor hawkins#foo fighters#drummers#pop rock#post grunge#rock#alternative rock#hottest Drummer tournament#The hottest Drummer tournament#Tournament#poll#poll tournament#Taylor hawkins and the coattail riders

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

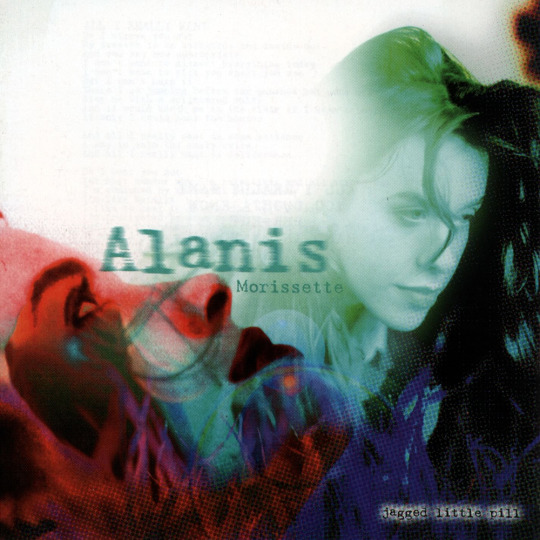

Swallow This Down: Alanis Morissette is 50

You oughta know today is Alanis Morissette’s birthday.

And here’s a jagged little pill for those feeling their age: Morissette is 50.

Born June 1, 1974, the Canadian singer reached the nifty milestone at midnight local time. And though she released two pop albums prior and seven more with such titles as Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie and the Storm before the Calm, subsequent to it, Morissette is, and will likely always be, best known for 1995’s Jagged Little Pill.

The album arrived at the right time and hit all the right emotional places for young people of the era.

And the music and performances hold up even if the subject matter - and the emotions it evokes - become less relational as the years fall away. ’Cause let’s face it, with the exception of Lauren Boebert, no one on the other side of 35 is going down on you in a theater.

Isn’t that ironic?

Given Morissette’s relationship with the word ironic, Sound Bites supposes it is.

6/1/24

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rudy Pankow para a FLAUNT MAGAZINE

| A máquina é de ouro maciço, sim, mas também maior que a soma de suas partes

Uma das minhas memórias menos queridas do ensino médio: a tarefa assustadora de recitar um monólogo de Shakespeare diante de toda a classe. Uma experiência verdadeiramente humilhante. Muito poucos de nós entenderam o significado por trás das palavras que decretamos — estávamos apenas nos esforçando para pronunciá-las corretamente e garantir uma nota decente. Depois de entrar em uma chamada do Zoom com o ator Rudy Pankow, pela primeira vez, quero voltar para a escola para tentar realmente dar sentido a essas palavras complicadas e canonizadas. “O mais bonito sobre Shakespeare é que se você confiar nele”, diz Pankow com um sorriso, “as palavras farão todo o trabalho.”

O ator que em breve completará 26 anos, que ganhou fama com a série de sucesso estrondoso, Outer Banks , está entrando em uma nova era. Agora podemos assistir Pankow ao vivo — sem cortes, sem refilmagens — enquanto ele abraça sua estreia no teatro neste outono como Romeu no clássico atemporal Romeu e Julieta . Até agora, Pankow não tem medo de ser cru, abraçando a imprevisibilidade e a autenticidade que somente o teatro ao vivo pode oferecer. “Você pode sentir uma grande diferença na tensão na sala”, ele lembra de arrasar em uma cena com uma plateia em uma de suas aulas de atuação teatral. “O momento em que a plateia ri, o momento em que a plateia respira com você. Você consegue estar na viagem com eles.”

Pankow estrelará ao lado de Emilia Suárez (Up Here, A Good Person) como os personagens-título no American Repertory Theater da Universidade de Harvard. Lançando a temporada 2024-2025 do teatro, a produção é dirigida pela vencedora do Tony Award Diane Paulus (Jagged Little Pill, Waitress, Pippin), que está se reunindo com o diretor e coreógrafo duas vezes vencedor do Olivier Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui (Jagged Little Pill, Babel(words), Puz/zle ) para encenar a tragédia clássica.

Em nossa ligação, Pankow está de volta à sua cidade natal, Ketchikan, Alasca, aproveitando um breve descanso de sua agenda agitada. Ele está preenchendo seus dias de verão praticando wakeboard com amigos e descansando. No entanto, é evidente que ele está ansiosamente esperando sua viagem para Boston na próxima semana para começar os ensaios. “Eu sempre quis fazer Shakespeare. É o padrão de ouro do teatro”, ele reflete. Seu treinador de palco Larry Moss sempre achou que ele seria um bom Romeu, então conseguir o papel é um momento de círculo completo.

A tragédia de Romeu e Julieta pode parecer uma história antiga e fora de sintonia, mas Pankow nos convence de que seus temas de amor, conflito e responsabilidade pessoal são mais relevantes hoje do que se poderia pensar. “Você tem um mundo ao seu redor ao qual pode prestar atenção, o que é importante, certo?”, diz Pankow, referindo-se à mensagem que espera transmitir, “Mas então é muito importante realmente focar em como controlar seu próprio mundo.”

Enquanto Romeo marca uma nova fase significativa para o ator, os fãs estão mais familiarizados com a interpretação de JJ por Pankow no já mencionado Outer Banks . Nas praias ensolaradas da Carolina do Norte, as aventuras de JJ são cheias de ação, camaradagem e a busca incansável por tesouros. Na terceira temporada mais recente, JJ e os Pogues continuam sua busca pela fictícia Cruz de Santo Domingo, enfrentando adversários perigosos e descobrindo segredos ocultos.

Outer Banks tem sido enorme para a Netflix, com todas as três temporadas aparecendo consistentemente na lista semanal Global Top 10 do serviço de streaming. A série ganhou vários prêmios People's Choice e MTV Movie & TV, um dos quais foi dado a Pankow por ‘Melhor Beijo’ em 2023. Para a alegria de muitos fãs, Pankow acabou de encerrar as filmagens da quarta temporada. Embora ele mantenha os detalhes em segredo, ele provoca com uma dica do que está por vir: “A manivela só gira em uma direção, então é maior, é mais intenso, mais reviravoltas estão por vir.”

Interpretar JJ é especial para Pankow; não há outra maneira de dizer isso. “O que é tão bom em construir um personagem é que você pode criar coisas novas”, ele diz. O espírito de JJ é inspirador e cativante, não apenas para o público, mas também para o ator. De certa forma, JJ foi uma espécie de professor para Pankow. “Ele nunca tem vergonha de resolver as coisas com as próprias mãos”, ele diz rindo. “Acho que ele me ensinou que é tipo, 'Ei, pegue o touro pelos chifres e tente segurar o máximo possível.'”

Com a nova temporada se aproximando, Pankow reflete sobre a jornada que seu personagem tomou nas últimas três temporadas. JJ começa como um pouco delinquente, sonhando apenas em viver na praia em Yucatán e evitar as complexidades da vida. No entanto, as aventuras e os desafios dos Pogues o forçam a crescer e assumir responsabilidades, transformando-o em um personagem determinado e confiável. “Neste ponto, acho que ele quer construir seu futuro; ele quer ser responsável por si mesmo, e esse é o seu crescimento”, explica.

Pankow segue uma regra de ouro, que talvez todos nós devêssemos adotar: entender que erros serão cometidos. Ele não está falando apenas sobre contratempos ocasionais; ele insiste que erros são inevitáveis — a parte crucial é como lidamos com eles. “Acho que, desde que você entenda essa regra de ouro, você deve ficar bem”, ele compartilha. “Eu me mantenho fiel a isso porque sei que não sou perfeito, mas também sei que quero fazer um bom trabalho em todos os aspectos da minha vida.” Não há como enquadrar Pankow. Ele não é um ator de ‘romance’ ou de ‘comédia’ — ele é um ator dinâmico. Ele apareceu anteriormente no filme da Sony Uncharted ao lado de Mark Wahlberg e Tom Holland, que arrecadou mais de US$ 400 milhões em todo o mundo. Ele também estrelou como protagonista no filme independente da Roadside Attractions Accidental Texan , ao lado de Thomas Haden Church, que ganhou o Texas Independent Film Award de 2024 da Houston Film Critics Society. Além disso, ele apareceu em 5lbs of Pressure, da Lionsgate , com Luke Evans, Alex Pettyfer e Rory Culkin.

Um belo currículo. Quando perguntado sobre como ele lida com a dinâmica diversa de cada conjunto, Pankow mergulha em uma analogia, “Não importa o quão diferente cada projeto seja”, ele diz, “a coisa mais importante a lembrar é que você é uma pequena parte do todo, uma engrenagem na máquina. Para que a roda gire, todos precisam trabalhar juntos, ouvir, entender e colaborar.” Ele continua, “É uma coisa tão linda quando todos estão trabalhando em direção a um objetivo comum, e eu tive a sorte de ver isso em primeira mão. O todo é realmente maior do que a soma de suas partes.”

Pankow entende que criar uma tapeçaria de emoções e experiências que ressoam profundamente com o público é uma questão de harmonia. Mas como essa harmonia acontece? O que faz as engrenagens da máquina girarem? Comunicação. Ele explica: "Se você está hesitando ou tem pensamentos que realmente não o levam a lugar nenhum, você precisa comunicar esses pensamentos, e é aí que todos nós começamos a girar.”

Essa confiança para se comunicar fala de uma espécie de bússola interna dentro de Pankow — não apenas usar sua voz quando necessário, quando precisa navegar pela relutância ou medo — mas ouvir. “Gostaria de aprender o máximo que puder”, ele comenta sobre onde vê sua jornada indo. “Gostaria de saber o que funciona e o que não funciona. Desde aprender sobre sets realmente grandes até aprender como um filme independente viaja longe se a equipe estiver, você sabe, girando as rodas.”

À medida que Pankow embarca em sua viagem para encarnar Romeu, seu processo nos lembra que, assim como a prosa duradoura de Shakespeare, a magia da narrativa está em sua capacidade de conectar as peças do quebra-cabeça da vida. E talvez, como eu, quando a "confiança" necessária ao ler Shakespeare canaliza através de alguém tão firmemente encravado no zeitgeist cultural moderno, você se verá querendo revisitar aqueles monólogos outrora assustadores com uma apreciação recém-descoberta pelo sempre romântico, sempre cômico Bard.

Via: Flaunt Magazine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I've sung her praises a gazillion times, but man...

I fucking love Jagged Little Pill era Alanis.

She was a revelation to this sheltered suburban boy.

She left such a lasting impression on me, it's incalculable.

"Hand In My Pocket" came up on shuffle, and I found myself sitting in my room in 1996 listening to that album, trying to absorb and understand it.

Like, I'd listened to female singers, you know, the usual suspects; your Whitneys Houston, Dollys Parton, Madonna...

But Alanis felt like something entirely modern...and mine.

Like she wasn't the kind of music you'd share with your parents.

And boy did she open some doors...

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Talk about Paige singing "Poor Thing" to Dean

“You'll never believe the nightmares, you'll never know the pain you caused.🎶

Let’s talk about 2.08 Shout part 2 mainly the moment Paige sings a poor thing to Dean requested lovingly by ashton (maya-matlin)!

So before the episode, our protagonist Paige was a different kind of girl, to say the least. We set the stage and mood. Paige was forever changed practically overnight for better and for worse this marks the rise of Paige.

Ashley’s poem 'poor thing' awoke something in Paige. It made her feel seen and felt. Despite being about something different it felt relatable and somewhat comforting. She resonated and played a big role in Ash’s pain. Earlier, Ashley had humiliated Paige (and let's be real: her own damn self) at the party in jagged little pill (1.15) by mid-season s2 in shout 1 and 2, they weren't best friends anymore and distant from one another. Ashley was far off on the outskirts with a new best friend Ellie and a new look to boot. Before long the cathartic poem Ashley had penned took on a whole new meaning.

As for PMS (Paige Michalchuk and the sex kittens), the lineup included Terri, Hazel (Spice), Paige, and Ashley. It was a miracle they made it happen between friction between Terri and Paige at rehearsals, tone-deaf Hazel’s surprise case of polyps, the lyrics debacle, and other mishaps the new and improved PMS finally took the stage.

PMS led by Ashley who was prepped on keyboards and ready for the solo, what could possibly go wrong? Enter Dean. Paige freezes and turns to Ashley for support, and lets her know she can't perform and that he is here watching the concert. Ashley is initially surprised when Paige starts acapella, by speaking the first words of the poem and eventually turns to face the audience and her perp with a strum of the guitar. She was going to destroy him.

Paige was also supported by Terri on background vocals and bass and Hazel on tambourine. I guess no one was on drums. (Just wanted to point out, Ellie 'suddenly' had a talent for percussion in season 5 'playing for her whole life' My ass! Obviously, her secret drum talent only exists bc of Craig 🙄 just kidding. However, when PMS rebranded as hell hath no fury in rock and roll high school a year later, she took on the bass. I'll be chalking it up to writers with selective memory, a retcon, and plot convenience. or some unfortunate continuity error. Missed opportunity.)

Important to note, she is singing directly at Dean, and it's satisfying to the audience and most likely Paige herself. I believe she was empowered by this, it was closure and her way of triumphing over him and what he had done to her and she used Ashley's lyrics which she had fought so hard to change. It was the best possible outcome of a power play. I couldn't be more proud of Paige and her ability to wield her power and influence. It is up Paige’s alley to do such a thing, but she used her powers this time for good as opposed to petty influence towards Hazel and Terri, and even Ashley at times. This marks a new era for Ms. Michalchuk, and we love to see it. This drives her to significantly grow and experience some major character development. It is awesome. This definitely holds up, it becomes cathartic and so pretty genius props to the writers for this. Embarrassed and humiliated publicly, the 'strong' 'emotionally challenged' Dean cowardly leaves like a dog, defeated with his tail between his legs. I spy the blind lady on the judge's panel she really seemed to enjoy the performance. Two men were seen rocking out beside her. I guess Big Bad bully Dean wasn't made of stone. He displays a semblance of blank and possible regret. He likely thought his presence would intimidate Paige but it only proved to empower her.

Ellie was a spectator to this performance and later offered her support to Paige at school. Although Poor Thing was cited as an honorable mention, she thought PMS was robbed. They were, let’s be real. Now I take this time to note, it's unclear why Ellie the next season wasn't so keen or nice to Paige such as in s3 a whisper to a scream when they were 100% rivals. It is nice and refreshing to see Ellie and Paige being cordial and not exchanging petty blows, cheap shots, and snide remarks like they typically do. While they won't be caught dead braiding each other's hair or going for mani-pedis, their relationship is at best conditionally chummy, with the occasional hints and moments of friendship scattered through. I'm not sure how they handled being roommates later on in life. Poor Marco was likely the mediator and peacemaker between the frenemies. He was a saint, God bless! Although sometimes Ellie and Paige surprised us as an audience such as with the bacon-y kiss in s7 and some heart-to-hearts when it counted. They had come so far in their evershifting dynamics.

Ashley deserves a medal for not being well, typical Ash, and making things about herself and instead stepping out from the spotlight for Paige to shine center stage. She also displayed genuine compassion for Paige as she embraced her and consoled her by the lockers when she told her what had happened, and why she felt so strongly about the lyrics in so many words. Sometimes they're too alike in their stubborn and hard-headed ways, unable to back down even when they’re dead wrong. However, despite what had happened between her and Paige over the last few months she didn't hold it against her and they buried the hatchet and even became friends again.

As Paige makes her way to Sauve's office she seems optimistic and ready to talk. </cue freeze frame. 👏 👏 👏

The end. Thank you for the ask. 💌

#degrassi#post#edits by brimi#prose#dtng#dtngedit#poor thing#paige michalchuk#dean walton#ashley kerwin#terri macgreggor#hazel aden#ellie nash#yes i made accompying graphics#can you believe this episode is 20?!#pms#paige michalchuck and the sex kittens#2003#00s#nostalgia#episode review#art#fanart#ask#maya-matlin#i'd like to do more of these#send more degrassi/eps scenes#💌 thanks for the ask!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

album game!

Massive thanks to @klove0511, @spice-and-lemonade, and @zombiejunk for tagging me (it's like y'all know I'm really into music or something). Apologies for the delay in responding, rewrites on the WinJess novel are eating my face but I feel like I've made enough progress today to take a quick break.

The Game: post your ten favorite albums of all time and tag ten people. My usual disclaimer to this sort of thing applies—there's no way I'll ever be able to pick ten all-time favorites, but here are some of them:

Poe - Haunted

Nickel Creek - Why Should the Fire Die?

Garbage - Garbage

Alanis Morrisette - Jagged Little Pill

Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice - Jesus Christ Superstar

Lady Gaga - The Fame/Monster

Bitter:Sweet - The Mating Game

The Talking Heads - Stop Making Sense (Live)

In This Moment - Ritual

Florence & The Machine - How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful

UGH at first I was like "will I be able to think of ten?" and now of course I'm like "but...there's at least twenty more I need to put on here..."

Also, this really made me reflect on how my listening habits have changed in the Spotify era. I think the newest album on here is from 2015? and most are from the 80s and 90s, a couple from the 2000s. I actually listen to a fair amount of current stuff too, but I mostly hear it through Spotify recommendations and occasional bangers people play at the pole or yoga studios, so there's much less impetus to seek out and listen to a whole album. I've noticed a lot of current artists releasing their work almost entirely as singles or EPs, probably for that reason—or they release regular albums but only one or two tracks on each one really stand out (Poets of the Fall, I'm looking at you).

No pressure, but if you'd like to play: @blahblahblahcollapse, @introvertia, @trashcangimmick, @sirsparklepants, @skybound2, @ihni, @degenderates, @sugaraddictarchangels, @spnyuri, @keziahrainalso, @soulless-puppy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Bloody Valentine - Loveless

The process of recording this album was insane. They went through nineteen producers before Kevin Shields decided to produce it himself. Bilinda Butcher was apparently woken up in the middle of the night to do vocal takes so she would sound authentically tired. And the band just kept on spending money they didn't have and tormenting themselves and everyone around them until Loveless was finished. The result is the definitive shoegaze album. There are so many layers of guitar fuzz, hazy vocals, looping dreamlike noise. It is nearly impossible to discern even a single lyric. Loveless feels like falling asleep. Its a symphony of euphoric noise. A broken refrigerator lullabye. Perfect in every way. Every shoegaze band owes something to this album.

Neil Young - Harvest

The most overrated Neil Young album. I don't want commercially viable Neil Young I want angry depressed counterculture Neil Young. This is just soft rock. Really, really good soft rock don't get me wrong. Still it mostly lacks the punch of his rawer albums.

Bob Marley And The Wailers - Exodus

Bob Marley's magnum opus and probably the greatest reggae album. Exodus leans hard in two directions. The first half is made up of intense songs with religious metaphor regarding Marley's personal exile from Jamaica after an assassination attempt. The second half features beautiful songs about redemption and love for his home in Jamaica. It makes for a much more varied tone than most reggae albums and the title track might be the most intense song in the whole genre. Meanwhile Three Little Birds might be the most pure and wholesome song about loving your hometown that has ever been written.

N.W.A - Straight Outta Compton

Massive historic turning points are rarely as obvious as N.W.A's Straight Outta Compton. This group featured rappers MC Ren, Eazy E, Ice Cube, and Dr. Dre back when they were still teens. And there is a specific blend of styles that requires a closer look to understand the significance of. Way back in the 1980s hip hop groups were no stranger to politically minded lyricism or teenage antics. But most teenagery stuff was more party oriented and less violent, and the political stuff was more mature and eloquent. N.W.A talk about their political situation, but in a way that promotes violent teen bravado. They are more visceral but also more personal. There's something about living out a cop killing fantasy rather than having an intellectual discussion about it that is a much needed release. This is the start of hip hop's kayfabe era. Of course none of this qould have mattered if Dre, E, Ren, and Cube weren't also incredibly talented rappers. And the beats provided by DJ Yella, Arabian Prince, and Dre are perfectly punchy. They combine the funk traditions of 80s hip hop with a more aggressive sound that makes N.W.A stand out even more.

Alanis Morisette - Jagged Little Pill

Every time I listen to this album I find myself liking it a little bit more than last time. I wouldn't call it a top 100 albums masterpiece but it is good. Alanis Morisette sings as if she's experiencing each emotion for the first time. This is her greatest strength because it takes a standard love song like Head Over Heels into weirdly feral territory, and it turns You Oughta Know from a breakup song to a good excuse to get a restraining order. I feel like she is teally only a few steps away from making metal music and I would like the album even better if it did take those last couple steps.

#500 album gauntlet#my bloody valentine#neil young#bob marley and the wailers#N.W.A#alanis morissette

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

would you guys like to know what cds i just picked up at goodwill? it's an interesting bunch.

i found some fantastic finds ngl.

up all night by one direction (idk why i've been in a weird 1d phase, probably bc i never actually went thru one but it's always fun to own cds instead of just streaming the music imo)

the cheetah girls 2 soundtrack (absolute banger)

high school musical 2 soundtrack (obviously better than the first)

the phantom of the opera soundtrack west end version (an absolute steal)

jagged little pill by alanis morissette (in my sad angry girl era, apparently)

was also gonna get avril lavigne's under my skin album but it was just the case lol

there was also just a fuckton of christmas albums. idk who let all of them go, but i hope they didn't die and instead just converted to judaism :)

#personal#text#highkey i love owning cds#one time i found britney's first album along with a singles cd inside for baby one more time#some let go of their 90s collection and i died getting so many albums for just a dollar

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yesterday I remembered that Go Hyun Jung had put a Lana Del Rey song in her Instagram pictures so here's a list of artists that 8090s actors would listen to if they were young(er) and in touch with modern music :

Choi Min Soo - A$AP Rocky, Ghost

(He is definitely a rap fan. I'm sure 90s Choi Minsoo would have loved Rocky's fashion and lyrics. His homies swear they bish the baddest but he just bagged the worst one (true). He praise the lord and breake the law. You get it. But he would still like Metal or Rock so he'd listen to Ghost and oldschool Rock too)

Go Hyun Jung - Lana Del Rey, Ethel Cain

(She's a moody indie girlie for sure. Mainstream enough for recognition but she'd be thr person to listen to all the songs and post insta stories in a sepia filter. She would quote Lana lyrics all the time and has a secret coquette girlblogging tumblr account. Oh and she is an expert on lyrics and interpretation. She's your national anthem )

Chae Shi Ra - Taylor Swift, boygenius

(She is definitely the Talent squads biggest Swiftie. She collects versions and has the set list of the Era's tour memorized. She also listens to boygenius and the members as well as some country-adjacent white girl pop or pop-rock music)

Kim Hee Ae - Lorde, Adele

(She definitely listens to socially conscious and more niche, non-radio pop and likes ballads. She also likes Kendrick Lamar due to his lyrics and other alternative singers like Tove Lo and Mitski)

Ha Hee Ra - Twenty one pilots, Glass Animals, The Neighbourhood

(She likes her indie pop bands with the chill and aesthetic songs and the dreamy, carefree, melancholic vibes. She's always down for a little bit of dance and hip hop though, but mostly enjoys more indie, dreamcore albums)

Uhm Jung Hwa - Chappell Roan, Beyoncé

(She's the model r/popheads user and stans the gays and the girls, like, in a stereotypical way. I'm sure she has all Beyoncé albums memorized plus loves brazen and confident dance pop of all kinds)

Cha In Pyo - Bruno Mars, Kid Laroi

(He has a more basic pop taste but likes oldschool music packaged in a new way, and loves music that has a lot of saxophone elements. He does listen to rap but only if its white people friendly)

Choi Jin Shil - Olivia Rodrigo, Alanis Morissette

(She likes her pop rock and definitely shares the love for rock with her little brother, SKY a.k.a. Choi Jin Young (R.I.P. 💜). Jagged Little Pill is her holy grail and she plays GUTS up and down)

Kim Hye Soo - Charli XCX, Kylie Minogue

(brat. Enough said. No seriously I know she would love hyperpop)

Choi Soo Jong - Ed Sheeran

(Man likes guitar ballads like Photograph and Perfect and thats what he regularly listens to, along with music like Drake or Imagine Dragons)

#Spotify#SoundCloud#8090s talents#Basic pop boys are kinda chill tbh#Brat summer#Thoughts post#lana del rey#taylor swift#ed sheeran#bruno mars#glass animals#twenty øne piløts#lorde#asap rocky

1 note

·

View note

Text

shade

The half-empty shampoo bottle slips from her shaking grasp. Lands with a cracking thud on the cool tile, plastic shell separating in a jagged line. A trail of blueish fluid spins out in a hypnotizing spiral as momentum sends it skittering across the ground. Slides right under the rungs of the bunk bed, all the way back against the wall where it’s unreachable.

Mess. Mess, mess, mess. Just a big fucking mess. Just another fucking mess.

One more thing she has to do, one more thing she needs to handle, to clean up. Another task between her and freedom — which is so, so close she could actually taste it. Bittersweet on her heavy tongue, rich like butterscotch candies and honeysuckle-nostalgia. Enough sugar to decay.

And it does. Rots into memories of better things, good things, sweet other freedoms: sitting in the shade under a willow in North Carolina on her grandparent’s farm. Sitting in the shade with her college friends outside the student union at Penn, drinking overpriced taro milk tea and laughing about some celebrity gossip. Sitting in the shade of autumn with her mom and Isaac, knees knocking together as they rock the porch swing and watch the dogs yap at each others’ ankles through the crunch of leaves.

Shade has always meant safety. Somewhere to escape the heat of the sun, find a moment to cool off, rest and recuperate. She’s never before felt danger in the shadows; has always leapt across the wavering boundary of sunlight with no expectations but a temperate embrace of relief. Shade's shelter.

She doesn’t feel sheltered or embraced now. She fears.

The last twelve hours have made her realize this: she has never experienced real, true fear. It is much different than the race of her heart after a movie jumpscare and scream queen shriek; a snake on the hiking trail; the bubble of excitement in the arm-raise drop on a Coney Island coaster.

Fear is the thing watching over her shoulder. Fear is men with guns that know how to use them, who use fists and knives otherwise. Fear is the gentle threat of her mother’s address being recited with chilling accuracy.

Matilda drops to the ground, ignoring the jab of pain in her knees. She could fall into that sting, do something with it, burst into action.

She doesn't. Instead she soaks in the embrace of self-pity, cool like shade. Tears prick at her eyes — that’s good. It feels welcoming to turn from the sun, to hide, to weep. So she allows them to spill over and fall freely.

Her mind zooms out: imagines herself as a morose, baroque painting. Maybe framed in grainy 8mm, a gorgeous sexplotiation-era nun with running mascara. Wonders if she looks pitiful-pretty, slumped in a heap and crying, crying, crying.

She thinks about needing to wear long pants later; her shins will purple within the hour, skin blossoming with a nasty, deep bruise that’ll stick around much longer than it should. Take your iron pills, Matilda, and the voice sounds like her mother.

Oh, her mom. She wants a hug, wants someone to ice her sore legs, to rub her back and let her cry and tell her it'll fade into a distant memory. Because this whole fucking experience? It's just been a nasty, deep bruise.

All civilian contracts extended until further notice. Comply with orders and continue job operations as previously outlined. Indicate agreement and return to supervisory agent by below date.

It hadn’t been her signature on the bottom of the page. Someone had forged it. Forged it with care, too. Had her little twirling coil around the T and everything. That T makes her nauseous to think about.

God, does she feel stupid. Matilda can count the number of times she’s felt stupid on one hand.

It was just supposed to be a temp job.

0 notes

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription, so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction. A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”

At the end of The Fraud, Eliza encounters Mr. Bogle’s son Henry, who has grown disgusted with his father’s quietism and become a political radical. He reproaches her for being more interested in understanding injustice than in doing something about it, proclaiming:

By God, don’t you see that what young men hunger for today is not “improvement” or “charity” or any of the watchwords of your Ladies’ Societies. They hunger for truth! For truth itself! For justice!

This certainty and urgency is the opposite of keeping one’s mind open, and while Mrs. Touchet—and Smith—aren’t prepared to say that it is wrong, they are certain that it’s not for them: “This essential and daily battle of life he had described was one she could no more envisage living herself than she could imagine crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a hot air balloon.”

Whether they style themselves as humanists or aesthetes, realists or visionaries, the most powerful writers who were born in the Seventies share this basic aloofness. To the next generation, the millennials, their disengagement from the collective struggle may seem reprehensible. For me, as I suspect is the case for many readers my age, it is part of what makes them such reliable guides to understanding, if not the times we live in, then at least the disjunction between the times and the self that must try to negotiate them.

0 notes

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription, so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction. A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”